Research overview

Our lab is an interdisciplinary group of researchers based in the Center for Biotechnology and Interdisplinary Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. We are working to uncover general principles of cellular behavior. How can single cells, lacking any sort of nervous system, coordinate their movements to navigate diverse, often fluctuating environments, avoiding danger and seeking out resources and favorable conditions? We apply ideas and approaches from diverse fields including cell and developmental biology, biophysics, and evolution grounded in microscopy and computation, to address this question primarily in microbial eukaryotes (protists), using their unique biological features as a window onto problems that would be difficult if not impossible to address in traditional model systems due to evolutionary history or multicellularity. Currently, our work mostly focuses on the ciliate Euplotes, a cell that can walk across surfaces using leg-like appendages. Despite vast evolutionary distances, many cellular components and processes underlying cellular behaviors are shared across eukaryotic diversity, and many physical constraints such as those imposed by geometry, fluid mechanics, or diffusion are shared as well. By clarifying general mechanistic and evolutionary principles, we aim to enhance our ability to understand, predict, and control cellular behaviors, which play key roles in the function of many ecosystems and in health and disease.

How is sensorimotor activity organized across space, time, and environmental contexts?

Single cells can display remarkably sophisticated, seemingly animal-like behaviors, managing the flow of information and orchestrating intricate processes far from thermodynamic equilibrium in order to carry out proper biological functions. Indeed, cells can make decisions by sensing and responding to diverse cues and signals, execute coordinated movements and directed motility, and even solve mazes and learn. How do cells sense and respond to their environments, and how do patterns of subcellular activity give rise to behavioral responses? How complex is the behavioral repertoire of single cell? How and to what extent can we predict cellular behavior or infer cell state from behavioral patterns? To answer these and related questions, we are investigating the sensorimotor and algorithmic behavior of cells, primarily Euplotes (see Publications), but also amoebae and other protists. This work is developing new tools, both theoretical and experimental, for interpreting and drawing inferences from complex cellular behaviors while shedding new light on principles underlying cellular decision-making and behavior. We always keep an eye out for opportunities to extend our efforts to other interesting cells.

What are the mechanisms of coordination and decision making?

In individual cells, behaviors emerge directly from the joint action of chemical reactions, cellular architecture, and physical mechanisms and constraints within the cell and in its local environment. Understanding cellular behavior, therefore, requires integration across disciplines and scales of biological organization. As we are accumulating increasingly sophisticated and detailed understanding of the molecular components of cells, it remains stubbornly challenging to translate this knowledge into understanding of how cells work. Our lab uses experiments and theory to quantitatively investigate cell structure and dynamics to get at mechanistic principles of behavioral control: How do cells control complex behaviors?

Currently, our efforts are focused on how Euplotes coordinates its leg-like ciliary appendages (cirri) during walking motility. The animal-like body plan of Euplotes, its multifaceted behavioral repertoire, and its large size together make these cells ideal candidates for rigorous experimental study. The diverse motile behaviors of Euplotes arise from differential control of cirri, so we aim to determine the mechanistic basis of cirral coordination. What drives decision making? Where and how is relevant information encoded? What is the role of physical constraints? Euplotes motility involves deeply conserved eukaryotic cell components, so mechanistic insights here may generalize to other cells, highlighting aspects that may obscured by multicellularity or evolutionary history in other better-studied eukaryotes. Building on prior work (see Publications), our goal is to arrive at an integrative perspective on mechanisms of cellular behavior, linking cellular structure, dynamics, and decision making to understand how behavior is regulated across spatiotemporal scales of biological organization.

How does cellular behavior evolve?

Eukaryotes are defined by complex cell structure, which is fundamentally connected to complex cell function. Understanding how new cell architecture emerges in the course of evolution is a key task in addressing the question of how cellular behavior evolves. Ciliates, including Euplotes, with their astounding variety of ciliary arrangements and modes of motility, vividly illustrate this integral relationship between cell architecture and function. We are poised at an exciting time in biology where we have the opportunity to expand our understanding of mechanisms dictating cellular form and function to how these processes have been elaborated over the course of evolution. A long-term goal of our lab is to establish systems for conducting evolutionary-developmental biology in unicellular organisms. Can we uncover how, for example, the size, number, and position of cellular appendages are specified and how those developmental mechanisms are modified over the course of evolution? We are beginning to make some steps toward these ends by studying a previously undescribed species of Euplotes isolated during field work that exhibits dramatic phenotypic plasticity, including cannibalistic supergiant morphs, in collaboration with Patrick Keeling's lab at UBC.

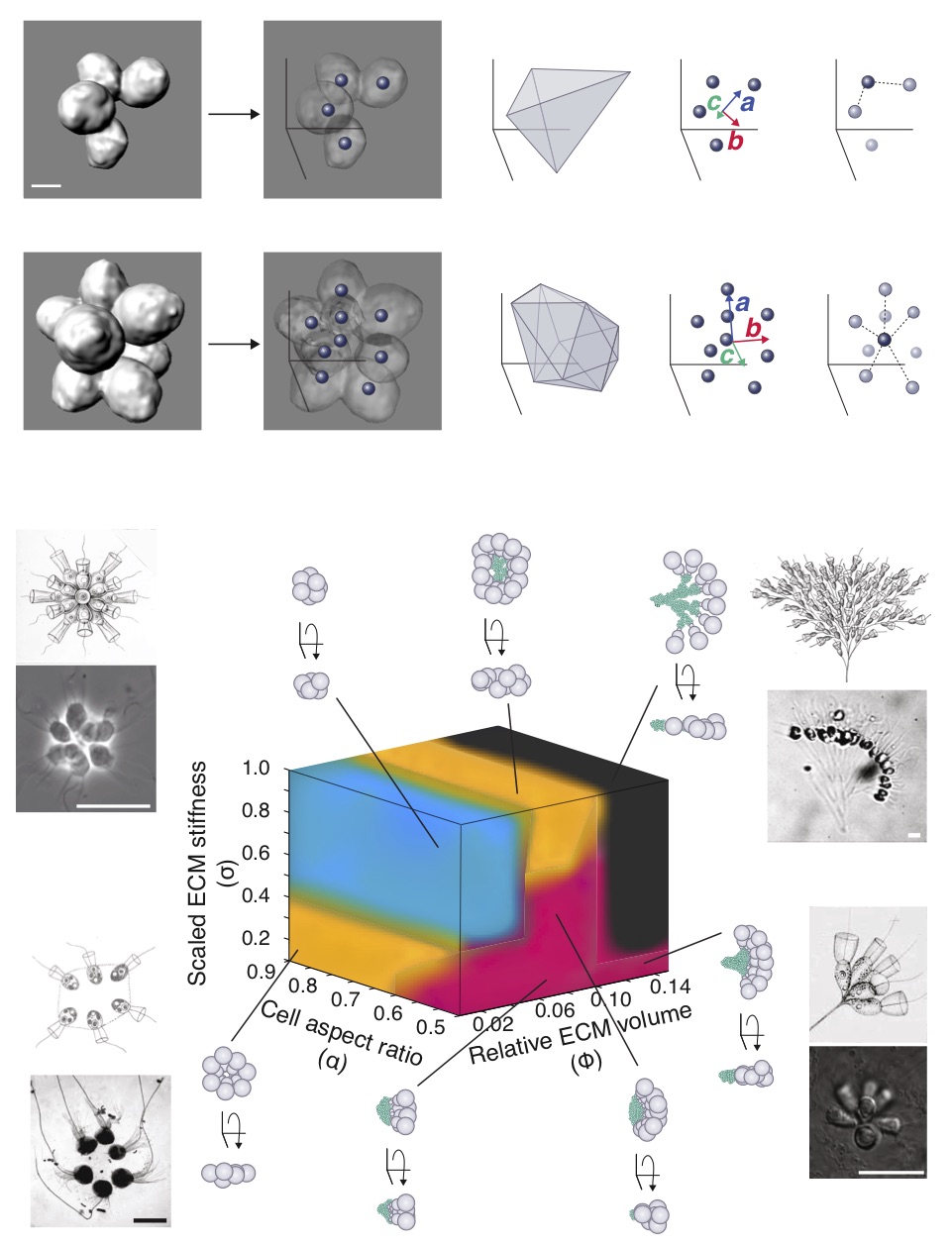

Principles of multicellular morphogenesis

Many organisms possess the remarkable capacity to reproducibly develop into 3D structures starting from a single cell. We seek to understand both the mechanisms by which multicellular morphogenesis is accomplished and in how such capacities evolve. In particular, we study how the regulated interplay between active cellular processes and physical constraints gives rise to the robust generation of form.

Various species of choanoflagellates, the closes living relatives of animals, can form multicellular colonies with different shapes, sizes, and behaviors. By comparing and contrasting the biology of choanoflagellates (and other protistan relatives) with that of animals, we are beginning to learn more about the evolutionary origins of animal multicellularity, including the evolutionary origins of developmental morphogenesis. My past work highlighted the role of the interplay between cellular behavior and physical constraints in giving rise to reproducible morphogenetic processes (see Publications). While my work focused primarily on a couple of species of choanoflagellates, my interests extend broadly to principles of morphogenesis. Our ongoing and future work aims to take comparative approaches, combining theory and experiments, to uncover principles of the regulation and evolution of morphogenesis.

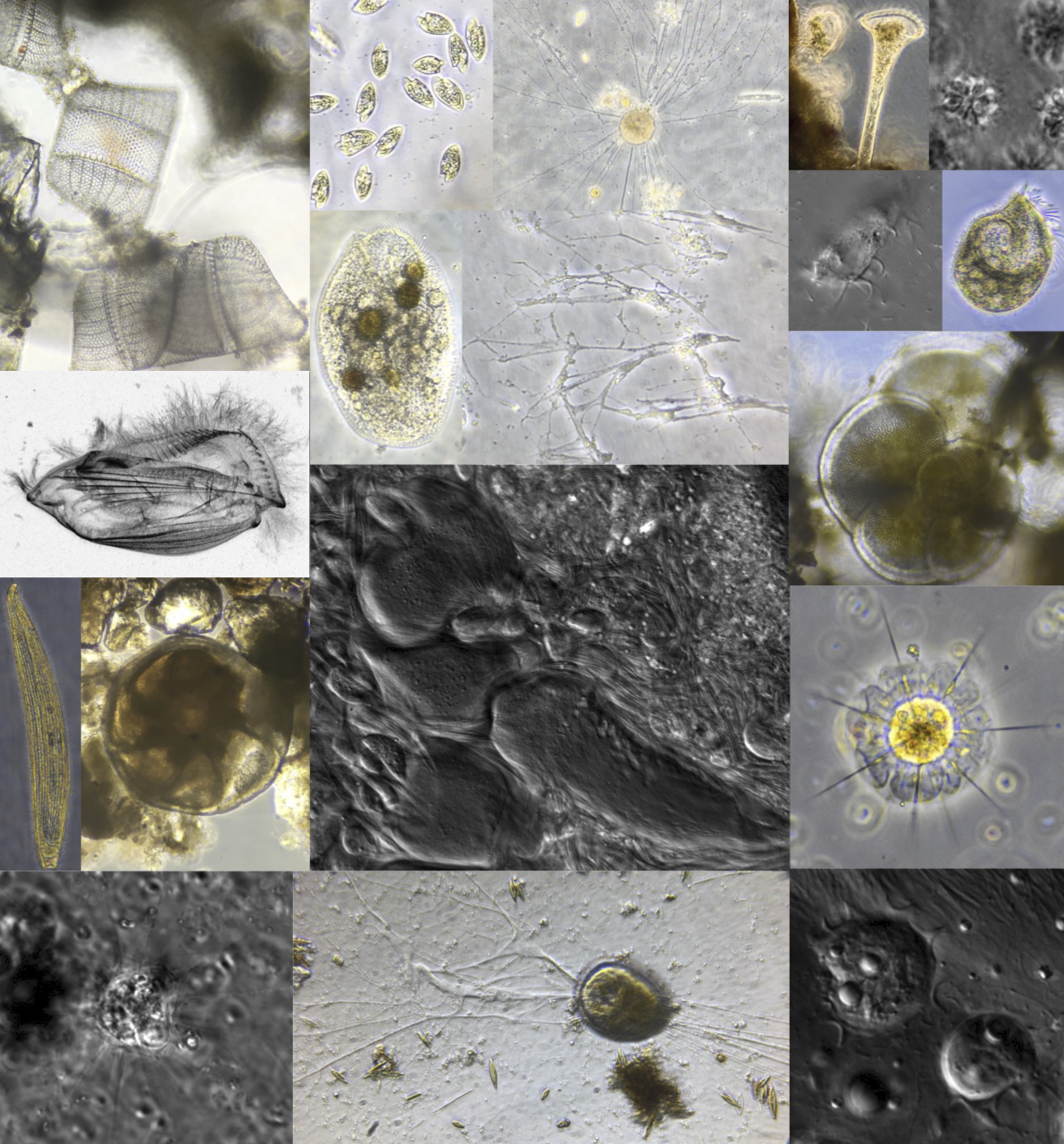

Natural history of protists

Much of the diversity of protists remains completely uncharacterized. Just about any field sample might contain a cell that could lead to important insights into fundamental biological questions. Although genomic and transcriptomic approaches can provide an important window on microbes in the environment, there is no substitute for the relatively slow approaches of careful observation and cultivation of cells, particularly when it comes to protists where cellular structure and function are difficult if not impossible to infer from a genome or transcriptome alone.

Our specific research questions may evolve, but we are always on the lookout for fascinating critters and the new questions they might inspire. In fact, many current research directions have been influenced by observations or discoveries made in the field. Furthermore, an appreciation for the natural context of biological function and what Barbara McClintock referred to as a "feeling for the organism" developed through close and careful observation are key factors in hypothesis generation and experimental design.